Article: ‘Logging scars’ show impact of deforestation in Canada is worse than we know, research finds

Read Full Article on Globe & Mail Canada Website. Posted December 3, 2019.

See our Sustainability Resources here.

After years of flying across northwestern Ontario on projects related to forest conservation, Trevor Hesselink has come to know certain features well. They consist of long lines and bare patches that thread their way through the bush for kilometres. Largely invisible from the ground, they form a widespread and persistent network of scars that reveal a little-known side effect of forestry practices.

“When you drive around up north and see all the trees whipping past you endlessly, you don’t really have a good idea of what’s going on,” said Mr. Hesselink, who is director of policy and research for the Wildlands League, a Toronto-based environmental not-for-profit.

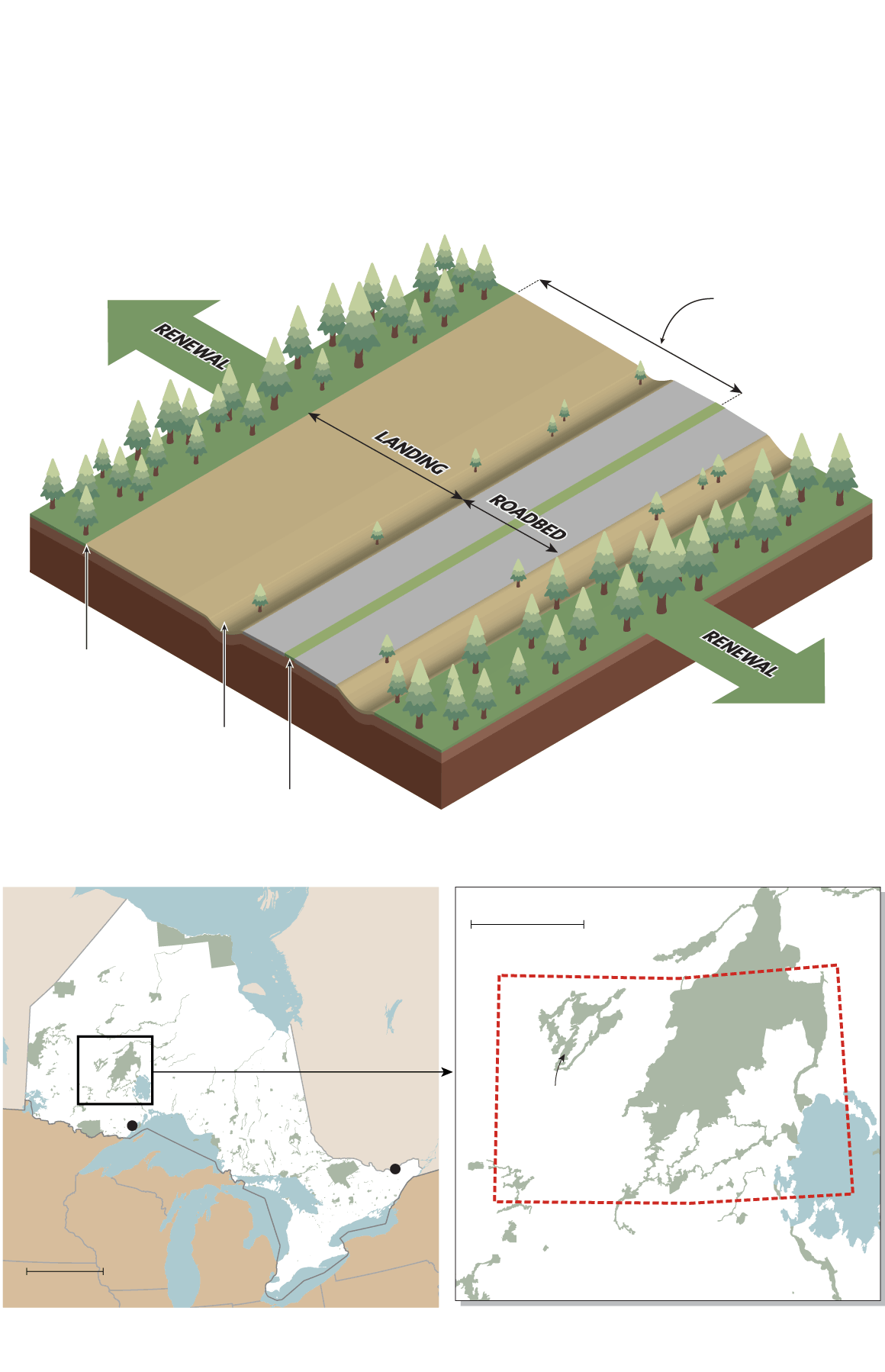

Together, a swath of roadway and adjacent landing area can measure 30 metres. This is narrow enough to be missed when large-scale remote-sensing surveys are used to measure the forest, but big enough to account for an estimated 21,700 hectares of deforested landscape in Ontario each year, the report found. This figure for Ontario alone is seven times greater than the reported rate of deforestation for all provinces combined, Mr. Hesselink said.

By 2030, it will amount to 41 megatonnes of carbon dioxide uptake loss – roughly equivalent to the total emissions for all passenger vehicles in Canada for one year.

“The idea that we’re not successfully regenerating trees on such large areas … I think would be disturbing to virtually anyone,” said Jay Malcolm, a biologist and forestry professor at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the report.

The findings are particularly troubling because much of Canada’s old-growth forest continues to be harvested for single-use, throw-away products such as tissues, or for pulp – products for which alternative sources exist. And while researchers and industry know about logging scars, no attempt has been made to rigorously quantify their impact until now.

Anthony Swift, a project director with the U.S.-based Natural Resources Defense Council, said the report has global implications because Canada’s boreal forest is considered the largest intact forest on Earth, with an amount of stored carbon that nearly doubles that in all the world’s known oil reserves. He said the report’s findings are another reason forestry should be further restricted. “As we face the need for urgent climate action, it is critical that we ensure that carbon stays where it is and isn’t released into the atmosphere,” he said.

Dr. Malcolm added that forest scars could have even more troubling effects, because in addition to reducing stored carbon, preliminary studies suggest the decaying debris at landing sites is also a source of methane, another potent greenhouse gas.

In a natural forest, regrowing vegetation would likely use the decaying material. He said the answer is straightforward: Regulators must keep a closer eye on forests long after logging occurs and require the industry to adjust its practices and minimize scars.

What is missing from this picture, Mr. Hesselink said, is an appreciation for how much, and for how long, tree growth is inhibited in places where heavy machinery has compressed the soil, or where the ground is inundated with waste wood from industrial-scale logging.

This is primarily conducted as “full tree harvesting,” in which a tree is severed at the base and dragged to a roadside landing area where limbs and tops are removed and often left behind. The soil under the temporary roadways that enable this practice is compacted to something approaching the hardness of asphalt. Seedlings have difficulty finding purchase along these routes, unlike in the surrounding clear-cut areas. The rectangular landings, which are similarly disturbed and can be choked with debris, also suppress tree growth, even after 30 years.

Read Full Article on Globe & Mail Canada Website. Posted December 3, 2019.